Germany's Oil and Gas Twilight

Contrary to a recent claim by a Berlin energy economist, Germany does not solely import its fossil fuels. My experience in the German E&P sector indicates that domestic production plays a small role.

Germany's exploration and production (E&P) sector is shrinking. Domestic oil production dipped by 3.7% year-on-year in 2023, while gas production plummeted by a steeper 12.6%. The decline rates observed in Germany's E&P sector are largely in line with natural production decline, given the lack of new field discoveries, enhanced recovery techniques or increased drilling activity, please refer to my recent post1. Despite these declines, Germany still managed to produce 1.6 million tons of oil (roughly 11.8 million barrels), meeting only 1.8% of its total oil needs. Its top three oil producing fields are:

Mittelplate/Dieksand (6.6Mbbl, 54% of Germany’s total oil production)

Emlichheim (0.9Mbbl, 8% of Germany’s total oil production)

Rühle (0.9Mbbl, 7% of Germany’s total oil production)

The picture worsens when considering reserves. While new discoveries partially offset annual production, Germany's overall reserves translate to roughly 14 years of production at current rates. These reserves are concentrated in Lower Saxony and Schleswig-Holstein.

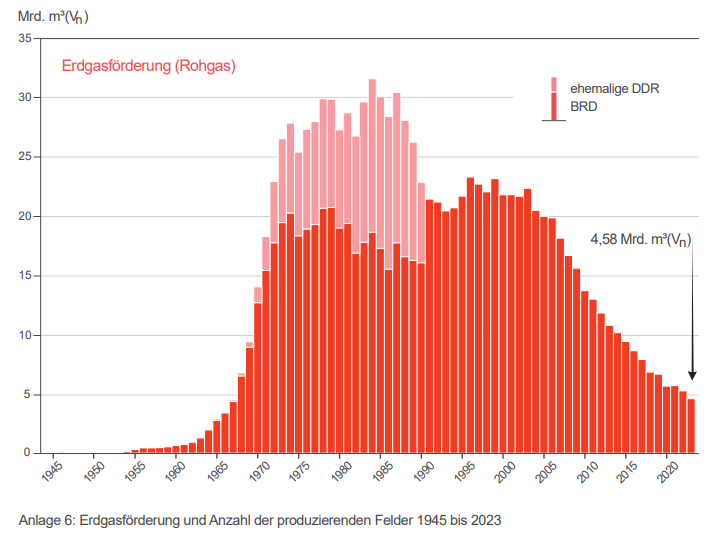

Natural gas presents a similar story. Reserves equate to approximately 7.8 years of production at 2023 levels, with Lower Saxony dominating production. 2023 gas production was around 4.6m3 (Vn) in 2023, which equates around 5.2% of Germany’s gas needs covered by domestic production. Lower Saxony is Germany’s gas production hub, the top three producing gas fields are:

Rotenburg / Taaken (545Mm3 (Vn), 32% of Germany’s total oil production)

Völkersen / Völkersen Nord (359Mm3 (Vn), 21% of Germany’s total oil production)

Söhlingen (198Mm3 (Vn), 12% of Germany’s total oil production)

Exploration

Good news is that there are still wells being drilling. However, overall exploration activity is sobering. And without any new exploration, now new discoveries can be made and new fields can be brought online to offset or defer natural production decline.

Exploration licenses:

Issuance of new exploration licenses stagnated in 2023, with relinquishments offset by new permits.3D land/marine seismic: Seismic surveying, a crucial tool for exploration, came to a standstill in 2023 both on- and offshore, offshore is also constrained due to stringent environmental regulations2

Exploration drilling: Only one new exploration well, Schwarzbach-2, was drilled in 2023, encountering oil-bearing rock but ultimately yielding low flow rates.34. Due to technical issues, the well was side-tracked. The well is operated by Rhein Petroleum, which is owned by Beacon Energy.

Legacy exploration wells: results from three more wells were disclosed

Lünne 1/1A: exploration well drilled by EMPG targeting the wealden and Poseidon shales regarding shale gas potential. Interesting well, since fracking is not permitted in Germany5

Schwegenheim 1: Drilled in 2019 by Palatina in the Upper Rhine valley targeting a Roemerberg analogue, to explore Buntsandstone, Muschelkalk & Keuper for oil. Production testing done.

Adorf Z17: Drilled by Neptune Energy in 2022 targeting gas-bearing fluvial sandstone (Stefan, Westfal)

Production drilling: 16 wells were drilled 2023, plus an additional seven legacy wells from previous years. Eleven results were released, 2 gas wells, 11 oil wells

On the bright side, fiscal framework for oil & gas concessions with small discoveries remains attractive.

The future

The only new hydrocarbon field to come online anytime soon, is most likely the offshore gas field N05-A6 straddling the Dutch-German border. It is facing some headwind7 at the moment, though permitting seems to progress8.

For the years to come, following topics are on the agenda for my German E&P players:

Decommissioning

Decommissioning and well abandonment will become a significant aspect of Germany's E&P sector as production declines.

Emission reduction

Additionally, reducing emissions will be a major challenge. Practices like steam flooding for heavy oil production and the operation of combined cycle power plants contribute significantly to CO2 emissions. Examples for heavy oil fields are Emlichheim, Georgsdorf or Rühle, where steam flooding is driving up CO2 emissions per barrel of oil produce. Another potent greenhouse gas is methane leakage from infrastructure such as pipelines, wells or compressor stations, which has to be addressed. Also rising EUETS and Germany’s domestic carbon tax make emissions more costly

Consolidation of Germany’s E&P sector.

The future of Germany's E&P sector likely lies in consolidation. The current landscape is fragmented, with a mix of larger players like EMPG/BEB (Shell, ExxonMobil), Wintershall Dea's German assets (now Harbour Energy), Neptune alongside smaller operators such as Vermillion Energy. Consolidation is tricky due to complex legacy permits, though in the long-term it will bring down overhead costs and streamline decommissioning expenditures.

Geological Data Storage Act

The act mandates that legacy geological, geophysical and geochemical data must be made publicly available, keeping both companies and mining authorities busy. However, the public availability of legacy geological data, can aid in the ongoing energy transition by facilitating a more comprehensive understanding of Germany's subsurface potential regarding geothermics, gas storage facilities (natural gas, hydrogen) and carbon, capture and storage.

Offshore vs onshore E&P activities

Historically, Germany's exploration and production efforts have been predominantly onshore. However, offshore activities targeting the Rotliegend play close to the Dutch border are expected to persist. While offshore activities targeting the Rotliegend play will continue, they face significant challenges. Geologically, reservoirs contain high levels of nitrogen lowering the calorific value of natural gas. Moreover, large portions of the North Sea are designated as national parks, and the region is already heavily utilized for offshore wind energy and shipping, creating a competitive environment. Also local stakeholders frequently oppose new E&P developments.

With potential amendments to carbon capture and storage (CCS) legislation, offshore CCS could become more viable. Furthermore, these amendments might also pave the way for onshore CCS initiatives.

Conclusion

Germany's E&P sector is undergoing a strategic transition. While domestic production is expected to decline, it will continue to play a role in the country's energy mix. Despite this, the sector generated approximately €190 million in royalties for the 16 German state budgets in 2023. Over 6,000 individuals are employed in companies affiliated with the German BVEG (Industrial Association of Natural Gas, Oil, and Geoenergy).

Beyond domestic production, the German E&P sector has developed innovative technologies that are used globally. Notably, there is a growing emphasis on transferring expertise to the geothermal and carbon capture and storage sectors.

Three comprehensive reads to understand Germany’s E&P sector are published by LBEG9, BGR10 and BVEG11. It’s an interesting read, since the oil & gas assets are organised by German rivers.

References

Challenging the Status Quo: Reassessing Oil and Gas Decline Rates

Earlier this week, while perusing John Kemp's daily energy digest, I stumbled upon Mark Finley's commentary, What’s Happening to Oil Market Forecasts?. Two days later I delved into ExxonMobil's energy outlook until 2050 Two specific data points regarding hydrocarbon supply rates caught my eye. I'm still grappling with the origins of their 11% and 15% de…